🪟 ViewModels

ViewModels are as simple as they are invaluable in this architecture.

A ViewModel provides a simplified and organized representation of the data to display on screen.

Contents

- Only Data

- Screen ViewModels

- Entity ViewModels

- Partial ViewModels

- ListItem ViewModels

- Lookup ViewModels

- How to Model

- “What”, not “How”

- “What”, not “Why”

- Keeping It Clean

- No Entities

- Avoid ViewModel to ViewModel Conversion

- Avoid Inheritance

- Composition

- Realistic Example

- Conclusion

Only Data

In this architecture a ViewModel is meant to be a pure data object. It’s recommended that ViewModels only have public properties, no methods, no constructors, no member initialization and no list instantiation. This to insist that the code handling the ViewModels takes full responsibility for the data. This also makes it better possible to integrate with different types of technology. Here is an example of a simple ViewModel:

public class ProductViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

}

Screen ViewModels

Every screen can get a ViewModel. Here are some Screen ViewModels you might find in an application:

ProductDetailsViewModel

ProductListViewModel

ProductEditViewModel

ProductDeleteViewModel

These names are built up from parts:

- Starting with the

Entityname:

Product,Category - Then something

CRUD-related:

Details,List,EditorDelete - And it ends with:

ViewModel

Instead of CRUD actions, you could also use terms like Overview, Selector, NotFound, or Login:

ProductOverviewViewModel

CategorySelectorViewModel

NotFoundViewModel

LoginViewModel

Here is a code example of a Screen ViewModel:

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

public string Category { get; set; }

public string ProductType { get; set; }

public IList<string> ValidationMessages { get; set; }

public bool CanDelete { get; set; }

}

Entity ViewModels

You can also reuse ViewModels that represent single Entities, e.g.:

ProductViewModel

CategoryViewModel

For instance:

public class CategoryViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

Entity ViewModels might be reused among different Screen ViewModels, for instance:

/// <summary>

/// An Edit ViewModel using several Entity ViewModels.

/// </summary>

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

// Using Entity ViewModels

public CategoryViewModel Category { get; set; }

public ProductTypeViewModel ProductType { get; set; }

}

Entity ViewModels are a kind of Item ViewModel.

Partial ViewModels

Partial ViewModels describe parts of a screen, to keep overview of its sections, like:

LoginPartialViewModel

ButtonBarViewModel

MenuViewModel

PagerViewModel

They may or may not have the word Partial in their name. Here is a code sample of a ButtonBarViewModel:

/// <summary>

/// Partial ViewModel representing a ButtonBar.

/// </summary>

public class ButtonBarViewModel

{

public bool CanSave { get; set; }

public bool CanDelete { get; set; }

public bool CanCreate { get; set; }

public bool CanShowList { get; set; }

}

Each property in there says whether you can use a certain button or not.

The Partial ViewModels can be used in Screen ViewModels. Here some Partials are used in the ProductEditViewModel:

/// <summary>

/// Edit ViewModel with Partials

/// </summary>

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

// Partials:

public ButtonBarViewModel Buttons { get; set; }

public LoginPartialViewModel Login { get; set; }

}

ListItem ViewModels

ListItem ViewModels are similar to the Entity ViewModels but instead they might represent a row in list or grid. Here are some names they might get:

ProductListItemViewModel

CategoryItemViewModel

A CategoryItemViewModel could look as follows:

public class CategoryItemViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public string UsedBy { get; set; }

public bool CanDelete { get; set; }

}

So they can be different from the Entity ViewModels.

ListItem ViewModels can be used inside a ListViewModel:

/// <summary>

/// Example of a ViewModel using ListItem ViewModels.

/// </summary>

public class CategoryListViewModel

{

// Here, a ListItem ViewModel is used.

public IList<CategoryItemViewModel> Categories { get; set; }

}

Some list views only need an IDAndName DTO, a version of which can be found in the JJ.Canonical project:

namespace JJ.Data.Canonical

{

public class IDAndName

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

}

}

Here you can find IDAndName objects used in a ListViewModel:

/// <summary>

/// Example of a List ViewModel that uses IDAndName as the item type.

/// </summary>

public class CategoryListViewModel

{

// Here, IDAndName is used as a list item.

public IList<IDAndName> Categories { get; set; }

}

Lookup ViewModels

A lookup list can provide the data for drop-down select boxes or other controls, e.g.:

IList<IDAndName> ProductTypeLookup { get; set; }

It might be used in a Screen ViewModel like this:

/// <summary>

/// Edit ViewModel with a Lookup List in it.

/// </summary>

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public IDAndName ProductType { get; set; }

// Here is the Lookup ViewModel.

IList<IDAndName> ProductTypeLookup { get; set; }

}

How to Model

A ViewModel is an abstract representation of what is shown on screen. The idea for how to model them is:

A

ViewModelsays what is shown on screen, not how or why.

“What”, not “How”

A ViewModel says what is shown on screen, not how:

Therefore CanDelete may be a better name than DeleteButtonVisible. Whether it is a Button or a hyperlink or Visible or Enabled, should be up to the View instead.

“What”, not “Why”

A ViewModel should say what is shown on screen, not why:

For instance: if the business logic tells us that an Entity is a very special Entity, therefore it should be displayed read-only, the ViewModel might contain a property IsReadOnly or CanEdit, not a property named ThisIsAVerySpecialEntity.

The reason for displaying data read-only should not be a concern for a ViewModel or a view.

Keeping It Clean

ViewModels might only use simple types and references to other ViewModels. This keeps the ViewModel layer completely self-contained.

No Entities

For instance, a ViewModel in this architecture isn’t supposed to reference any Entities. This is because it would potentially connect the ViewModel to a database, which is not always desired or even possible.

Even when the ViewModel looks almost exactly the same as the Entity, we tend to not use Entities directly.

public class Product

{

public virtual int ID { get; set; }

public virtual string Name { get; set; }

public virtual Category Category { get; set; }

}

public class ProductViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public CategoryViewModel Category { get; set; }

}

It is worth noting that linking to an Entity can result in the availability of other related Entities, which may broaden the scope of the view beyond our intentions:

/// <summary>

/// This ViewModel references an Entity, which is not recommended.

/// </summary>

public class ProductViewModel

{

public int ID { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

// Not recommended: Referencing an Entity from a ViewModel.

public Category Category { get; set; }

}

// Unintentionally, many customers' data

// is available in the Product view,

// because we referenced an Entity.

var customers =

productViewModel.Category.Products

.SelectMany(x => x.Orders)

.Select(x => x.Customer);

An added benefit of decoupling the ViewModels from Entities, is that it makes it possible to change a ViewModel without affecting the data access layer or the business logic:

public class CustomerViewModel

{

public string CustomerNumber { get; set; }

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string CouponCode { get; set; }

}

public class Customer

{

public virtual int ID { get; set; }

public virtual string Name { get; set; }

public virtual string CustomerNumber { get; set; }

}

Here the Entity and ViewModel look completely different, which is totally fine.

Avoid ViewModel to ViewModel Conversion

It is not advised to convert ViewModels to other ViewModels directly:

/// <summary>

/// Conversion from ViewModel to ViewModel is not recommended.

/// </summary>

public static void Convert(

EditViewModel userInput, ProductViewModel viewModel)

{

if (viewModel.HasVat)

{

viewModel.Price = userInput.Price * userInput.Vat;

}

else

{

viewModel.Price = userInput.Price / userInput.Vat;

}

}

What we’re trying to prevent here is too much interdependence between ViewModels. Prefer converting from Entities to ViewModel and back:

Product entity = _repository.Get(id);

decimal price = entity.PriceWithoutVat * _taxCalculator.VatFactor;

var viewModel = new EditViewModel { Price = price };

This gives us finer control over where the data comes from and goes. But there might be exceptions. There could be cases, where it makes more sense to operate directly on the ViewModels instead:

public void ExpandNode(TreeViewModel viewModel, int id)

{

var node = viewModel.Nodes.Single(x => x.ID == id);

node.IsExpanded = true;

}

It may be about properties, that aren’t intended for permanent storage. You can also pass other non-persisted properties between ViewModel like this:

public QuizViewModel Answer(QuizViewModel userInput)

{

var viewModel = new QuizViewModel();

// Yield over non-persisted properties.

viewModel.SelectedOption = userInput.SelectedOption;

viewModel.AnswerVisible = userInput.AnswerVisible;

return viewModel;

}

Avoid Inheritance

Inheritance is not the go-to choice for ViewModels.

Using inheritance creating a base ViewModel can lead to a high number of interdependencies between the Views and the ViewModels. If the base ViewModel changes, it can potentially break many Views, making the application harder to maintain:

public abstract class ScreenViewModel

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Description { get; set; }

}

public class HomePageViewModel : ScreenViewModel

{

// ...

}

public class ProductEditViewModel : ScreenViewModel

{

// ...

}

Here the BaseViewModel contains the properties Name and Description. These properties might potentially mean something different for the HomePage and ProductEdit views. If we decide to rename the base properties to be more specific, or to change their purpose, we could be breaking multiple views, because we used inheritance.

By avoiding inheritance, a ViewModel can only break things that directly depend on it, reducing the potential impact of changes:

public class HomePageViewModel

{

public string PageTitle { get; set; }

public string UserDisplayName { get; set; }

}

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

public int ProductID { get; set; }

public int ProductName { get; set; }

public int ProductDescription { get; set; }

}

In these examples, each ViewModel is self-sufficient and does not affect the other.

To really ‘seal’ the deal, you could make the ViewModel classes sealed to prevent inheritance at all:

public sealed class HomePageViewModel

{

public string PageTitle { get; set; }

public string UserDisplayName { get; set; }

}

Though no hard rules here. It doesn’t mean that inheritance should always be avoided. It may still be possible to use inheritance in a way that is maintainable by applying it carefully:

public abstract class ScreenViewModel

{

public bool Visible { get; set; }

public bool Successful { get; set; }

public IList<string> ValidationMessages { get; set; }

}

By keeping the members in the base class very general, and not applicable to specific situations, it would be less likely to break as the software evolves.

Composition

As an alternative, you could also choose to use other design patterns, such as composition, to reduce the impact of changes:

public class HomePageViewModel

{

public ScreenViewModel Screen { get; set; }

public LoginPartialViewModel Login { get; set; }

}

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

public ScreenViewModel Screen { get; set; }

public ValidationViewModel Validation { get; set; }

}

The HomePage uses common properties and has a Login. The ProductEdit view uses common properties and has Validation.

ScreenViewModel and the ValidationViewModel are reused. ScreenViewModel defines common properties for any screen or page. The ValidationViewModel has properties for data validation, like ValidationMessages and a Successful flag.

By using composition, changes to a child object can still have an impact on multiple views. But the modular nature of composition allows for a potentially smaller scope of dependency than inheritance.

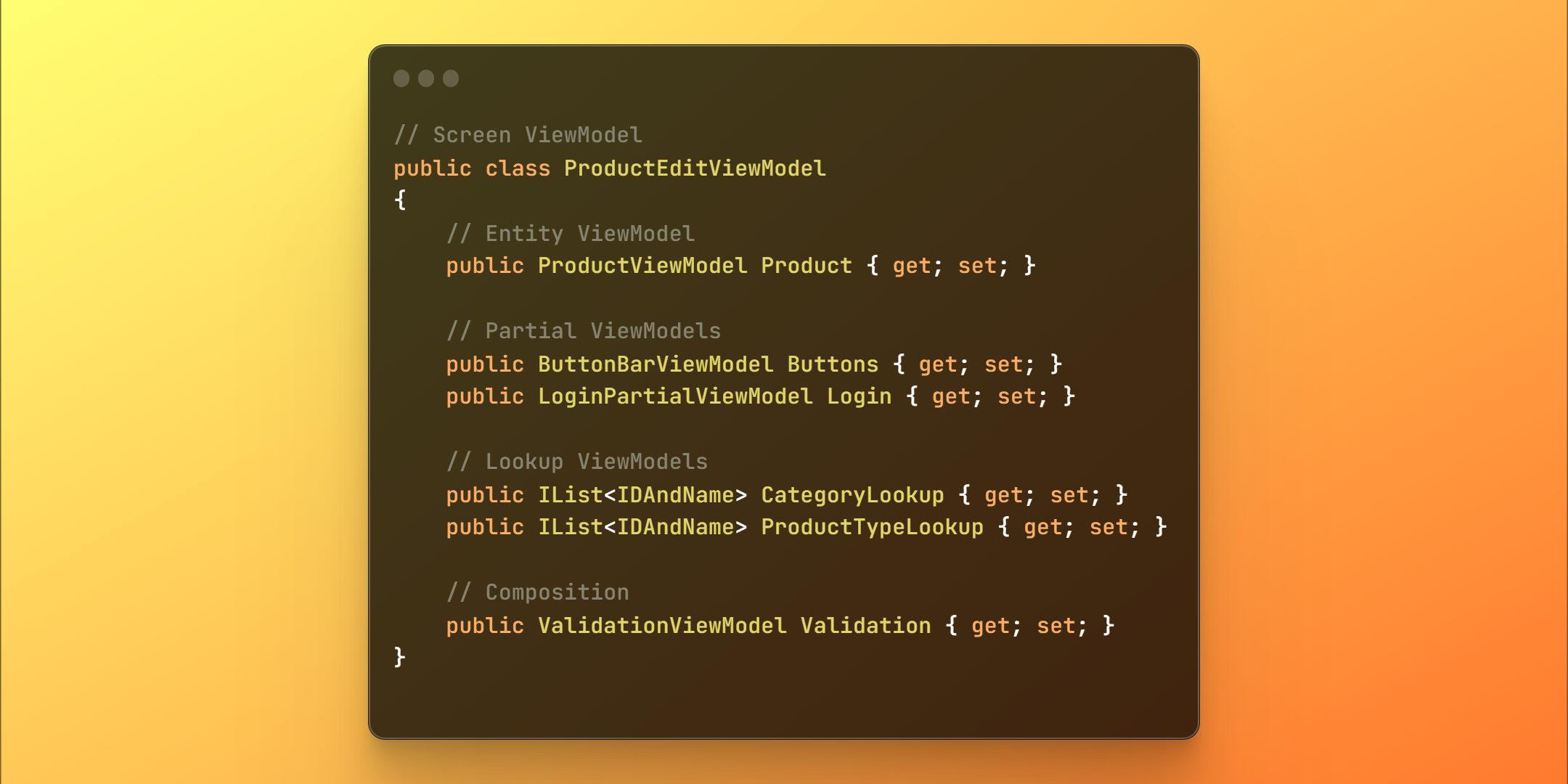

Realistic Example

Finally, here is a realistic example of a ProductEdit ViewModel:

// Screen ViewModel

public class ProductEditViewModel

{

// Entity ViewModel

public ProductViewModel Product { get; set; }

// Partial ViewModels

public ButtonBarViewModel Buttons { get; set; }

public LoginPartialViewModel Login { get; set; }

// Lookup ViewModels

public IList<IDAndName> CategoryLookup { get; set; }

public IList<IDAndName> ProductTypeLookup { get; set; }

// Composition

public ValidationViewModel Validation { get; set; }

}

Conclusion

Hopefully this gave a good impression of how ViewModels might be structured. They can enable technology independence, preventing hard coupling to business logic and data access, offering a flexible way to model the user interaction. In the coming sections, more patterns will be introduced, to illustrate how these ViewModels might be used in practice. To see where they come from and go.